Deep beneath the Earth's surface, in the labyrinthine fractures of ancient rock formations, scientists are uncovering a hidden world of microbial life that challenges our understanding of energy production. These subterranean communities, thriving in complete darkness and extreme conditions, may hold the key to a revolutionary concept: geocentric "dark energy" in the form of hydrogen-producing metabolic chains. Unlike the cosmological dark energy that propels the universe's expansion, this terrestrial counterpart represents a tangible, biological energy source with profound implications for sustainable technology and our comprehension of life's resilience.

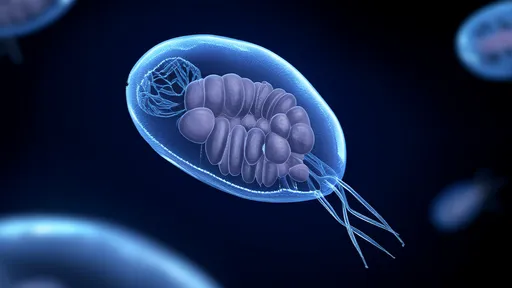

The discovery of hydrogen-generating microorganisms in deep rock fractures has rewritten textbooks on biogeochemistry. These extremophiles, existing without sunlight or organic carbon, derive energy through chemosynthesis – breaking down inorganic compounds in the rock itself. What makes them extraordinary is their ability to catalyze water-rock reactions that release molecular hydrogen, creating a continuous energy cycle that has potentially sustained these ecosystems for millions of years. Researchers drilling into Precambrian shield rocks have found hydrogen concentrations up to 30% higher in microbe-colonized fractures compared to sterile zones, suggesting active biological participation in hydrogen production.

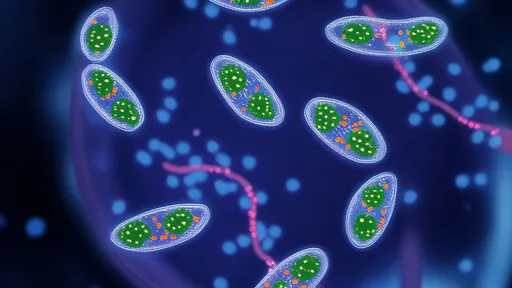

Metabolic alchemy in the deep biosphere operates through a complex interplay of geology and biology. Certain iron-rich minerals like olivine and pyroxene undergo serpentinization when water penetrates deep fractures – a geochemical process that normally produces hydrogen abiotically. However, microbial communities appear to accelerate this reaction through enzymatic pathways, effectively "farming" hydrogen as their primary energy source. The metabolic chain involves multiple microbial species working in concert: some bacteria extract electrons from ferrous iron in minerals, while others utilize these electrons to reduce protons from water molecules, completing the hydrogen-generating cycle. This intricate symbiosis creates what some scientists describe as a "subsurface hydrogen economy" operating on geological timescales.

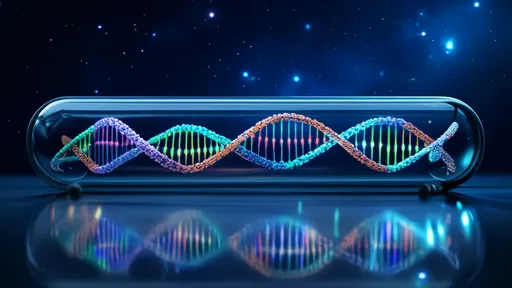

Recent isotopic tracing experiments have provided smoking-gun evidence for biologically enhanced hydrogen production. When researchers introduced deuterium-labeled water into microbe-bearing rock cores, the resulting hydrogen gas showed isotopic fractionation patterns inconsistent with purely abiotic processes. Even more compelling, genomic analyses of fracture-dwelling microbes reveal hydrogenase enzymes with unique structural adaptations to high-pressure environments – molecular tools perfectly suited for catalyzing hydrogen generation under extreme conditions. These findings suggest that subsurface microbial communities haven't just adapted to exploit existing hydrogen sources, but have evolved mechanisms to actively maintain and enhance hydrogen production in their environment.

The scale of this hidden hydrogen cycle could be staggering. Conservative estimates suggest the continental subsurface may harbor 10^29 microbial cells, with fracture networks extending kilometers deep in many geological formations. If even a fraction of these communities participate in hydrogen-generating metabolisms, the collective output could represent a previously unrecognized component of Earth's energy budget. Unlike surface ecosystems dependent on the trickle-down of solar energy, these deep biosphere communities appear to tap directly into planetary-scale geochemical processes, creating what amounts to a self-sustaining "dark energy" network operating independently of surface conditions.

Practical applications of this discovery are already emerging. Bioengineers are studying these microbial systems to develop more efficient hydrogen production technologies, potentially revolutionizing clean energy systems. Some experimental bioreactors using extremophile-derived enzymes have achieved hydrogen production rates exceeding conventional electrolysis methods. Meanwhile, astrobiologists point to these findings as evidence that similar hydrogen-based ecosystems might exist in the subsurface oceans of icy moons or within Mars' ancient crust, expanding the potential habitats for life in our solar system.

As drilling technologies allow access to ever-deeper rock formations, scientists continue to uncover new surprises about these enigmatic ecosystems. Recent discoveries include microbial communities living in 3.5-billion-year-old fractures in South Africa's Witwatersrand Basin, where hydrogen-producing metabolisms appear to have persisted with minimal genetic change over geologic epochs. This remarkable stability suggests that subsurface hydrogen cycles may represent one of Earth's most ancient and enduring energy systems – a living relic from our planet's earliest habitable period that continues to operate beneath our feet, largely unnoticed until now.

The implications extend beyond microbiology into planetary science and energy futures. If hydrogen-generating microbial networks indeed represent a significant geochemical process, we may need to reconsider models of Earth's deep carbon and energy cycles. Some researchers speculate that such systems could have played a crucial role in maintaining primordial atmospheres or even influencing plate tectonics through rock-weakening effects. As we stand on the brink of a hydrogen economy, nature's billion-year-old solution to sustainable energy production in Earth's depths offers both inspiration and caution – reminding us that our most revolutionary ideas often pale beside evolution's ingenuity.

By /Aug 7, 2025

By /Aug 7, 2025

By /Aug 7, 2025

By /Aug 7, 2025

By /Aug 7, 2025

By /Aug 18, 2025

By /Aug 7, 2025

By /Aug 7, 2025

By /Aug 7, 2025

By /Aug 7, 2025

By /Aug 18, 2025

By /Aug 18, 2025

By /Aug 7, 2025

By /Aug 18, 2025

By /Aug 7, 2025

By /Aug 18, 2025

By /Aug 7, 2025

By /Aug 7, 2025

By /Aug 7, 2025

By /Aug 7, 2025