The petri dish has long been a canvas for science, but in recent years, it has also become an unlikely medium for art. Across laboratories worldwide, microbiologists and artists are collaborating to visualize the invisible threat of antibiotic resistance through stunning, often unsettling, microbial art. These creations—grown from bacteria, fungi, and other microorganisms—serve as both a scientific tool and a cultural statement, merging the rigor of microbiology with the emotional impact of visual storytelling.

At the heart of this movement is a paradox: the very beauty of these living artworks underscores their danger. Vibrant swirls of Staphylococcus aureus or delicate branching patterns of Escherichia coli are rendered in vivid hues by chromogenic agar, turning resistant strains into abstract landscapes. Yet their aesthetic appeal belies a grim reality. Each colorful colony represents pathogens that evade our most potent drugs, a crisis projected to claim 10 million lives annually by 2050 if unchecked. Artists like Anna Dumitriu and biohacker Nuria Conde have pioneered techniques to "paint" with antibiotic gradients, where zones of inhibition form halos around drug discs—a stark visual metaphor for medicine's shrinking arsenal.

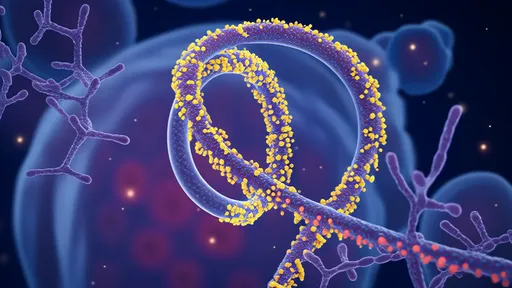

The process itself is a meticulous dance between control and chaos. Unlike traditional art forms, microbial compositions evolve unpredictably as colonies compete for resources or mutate mid-growth. Some practitioners exploit this by using genetically engineered bacteria that fluoresce under UV light, creating ephemeral installations that change hourly. Others, like the Micropia museum in Amsterdam, embed agar plates with antibiotics to demonstrate resistance patterns through living infographics. The resulting pieces—sometimes preserved in resin, other times deliberately destroyed after exhibition—challenge viewers to confront microbial intelligence on its own terms.

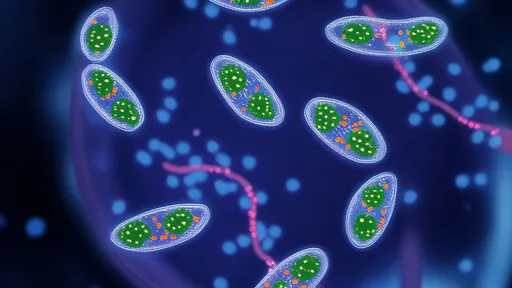

Critics argue such projects risk glamorizing superbugs, but proponents counter that they democratize science. When Harvard’s "Germ Art" exhibition displayed MRSA cultures alongside historical plague maps, visitors reported heightened awareness of resistance spread. Similarly, citizen science initiatives invite the public to "culture their environment," swabbing subway poles or smartphones to grow personalized resistance maps. This participatory approach has caught the attention of policymakers; the WHO’s 2023 report on antimicrobial resistance featured microbial artwork to emphasize surveillance gaps.

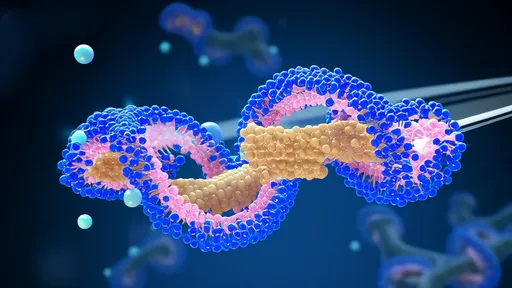

Beyond galleries, the techniques have unexpected clinical value. Researchers at Imperial College London adapted artistic plating methods to track hospital outbreaks, using color-coded strains to visualize transmission routes. Meanwhile, synthetic biologists draw inspiration from these patterns to design new antimicrobial surfaces. The crossover has birthed an entire aesthetic lexicon—terms like "bacterial bloom" and "resistance topography" now appear in both lab notebooks and exhibition catalogs.

Perhaps the most poignant works are those that incorporate human elements. A recent installation by artist-scientist Joana Ricou used agar mixed with tears from different emotional states to show how stress hormones affect microbial growth. Another project embedded antibiotics in agar shaped like ancient healing symbols, highlighting the fraught relationship between medicine and evolution. These pieces don’t just depict resistance—they make it visceral.

As the field matures, ethical questions surface. Should artists work with Level 3 pathogens? Can aestheticizing crisis lead to complacency? There are no easy answers, but the dialogue itself proves the power of this fusion. By rendering an abstract threat tangible, microbial art compels us to see resistance not as distant science, but as a deeply human problem—one demanding creativity equal to its complexity.

The next frontier may lie in augmented reality. Pioneers like the BioArt Lab at Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute are overlaying digital resistance data onto physical cultures, allowing viewers to "see" gene transfer between bacteria in real time. Such innovations suggest that the marriage of art and science will only grow richer as the resistance crisis deepens. In the end, these petri dish masterpieces do more than inform—they implicate. Every brushstroke of bacteria is a mirror held to our collective choices, a reminder that in the war against superbugs, humanity is both the aggressor and the endangered.

By /Aug 7, 2025

By /Aug 7, 2025

By /Aug 7, 2025

By /Aug 7, 2025

By /Aug 7, 2025

By /Aug 18, 2025

By /Aug 7, 2025

By /Aug 7, 2025

By /Aug 7, 2025

By /Aug 7, 2025

By /Aug 18, 2025

By /Aug 18, 2025

By /Aug 7, 2025

By /Aug 18, 2025

By /Aug 7, 2025

By /Aug 18, 2025

By /Aug 7, 2025

By /Aug 7, 2025

By /Aug 7, 2025

By /Aug 7, 2025