The field of synthetic biology has made tremendous strides in recent years, with engineered microbial strains now being deployed for applications ranging from pharmaceutical production to environmental remediation. However, as these designer organisms become more sophisticated, concerns about their potential escape into natural ecosystems have grown louder. Scientists are now racing to develop robust "biocontainment" strategies—biological safety locks—to prevent unintended environmental release of genetically modified microbes.

The Escapist Problem

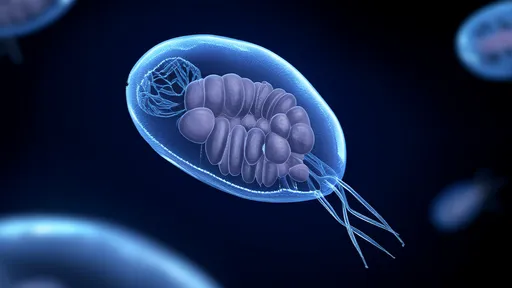

Unlike contained industrial bioreactors, many proposed applications involve releasing engineered bacteria directly into open environments. Oil-eating microbes for spill cleanups, nitrogen-fixing bacteria for agriculture, or gut microbiome therapeutics all require organisms to function outside controlled labs. This creates a troubling paradox: we need these microbes to survive long enough to perform their tasks, but not so long that they persist indefinitely or transfer synthetic genes to wild populations.

Early containment approaches focused on knocking out essential metabolic pathways, creating auxotrophic strains dependent on laboratory-supplied nutrients. While effective in theory, evolutionary pressure often leads to mutations that restore metabolic independence. Similarly, attempts to engineer "suicide genes" triggered by environmental signals frequently fail when rare mutant cells bypass the kill switch through genetic drift.

Next-Generation Biocontainment

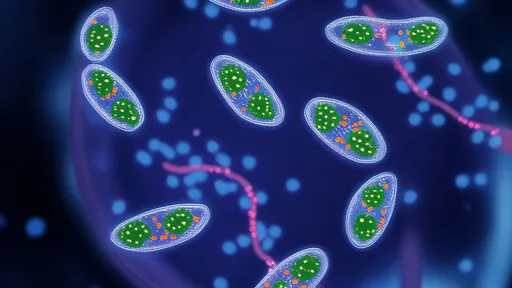

Modern synthetic biology approaches this challenge through multilayered redundancy. Harvard's George Church lab pioneered a "genetic firewall" concept where engineered bacteria rely on synthetic amino acids not found in nature. Without constant artificial supplementation, the microbes cannot build essential proteins. This xenobiological approach makes escape evolutionarily difficult since multiple synthetic building blocks would need to spontaneously emerge in the environment.

Another promising direction comes from CRISPR-based "gene drives" programmed to automatically delete key synthetic DNA sequences if bacteria escape defined parameters. California researchers recently demonstrated a system where engineered Pseudomonas putida strains self-destruct if they leave root systems of target plants, triggered by loss of plant-specific chemical signals.

Physical and Ecological Barriers

Beyond genetic tricks, some teams are exploring physical containment through synthetic cell membranes requiring artificial chaperone proteins to maintain structural integrity. Others design "Trojan horse" systems where the actual synthetic function is split across two microbial species—neither can perform the engineered function alone, dramatically reducing risks of horizontal gene transfer.

Ecological containment strategies take inspiration from nature's own barriers. By engineering microbial consortia that create mutual dependencies—like cross-feeding essential metabolites—researchers can ensure community collapse if any member escapes. This approach mirrors natural ecosystems where niche specialization prevents any single species from running rampant.

The Regulatory Tightrope

As containment technologies advance, regulators struggle to balance innovation with precaution. The European Union's recent synthetic biology framework requires progressively stricter containment for environmental applications, while U.S. guidelines remain more flexible for contained industrial uses. This regulatory patchwork creates challenges for global deployment of engineered organisms.

Critically, no containment system can be 100% failsafe. The synthetic biology community increasingly emphasizes "graded" containment—matching safety measures to specific risk scenarios. A probiotic for human guts might need different safeguards than bacteria designed to break down ocean plastics. This risk-adapted approach acknowledges that absolute containment may be impossible, but highly improbable escape can still achieve acceptable safety.

Public Perception and the Way Forward

Public acceptance remains a significant hurdle. High-profile cases like the 2016 Zika-fighting mosquito releases in Florida showed how community concerns can stall even carefully contained projects. Transparent risk communication and independent safety verification will be crucial as more engineered organisms transition from labs to real-world applications.

The coming decade will likely see containment strategies evolve from simple genetic switches to complex systems integrating synthetic biology, materials science, and ecological theory. As one researcher noted, "We're not just engineering organisms anymore—we're engineering entire fail-safe ecosystems." This holistic approach may finally provide the safety assurances needed to unlock synthetic biology's full environmental potential without unleashing unpredictable consequences.

By /Aug 7, 2025

By /Aug 7, 2025

By /Aug 7, 2025

By /Aug 7, 2025

By /Aug 7, 2025

By /Aug 18, 2025

By /Aug 7, 2025

By /Aug 7, 2025

By /Aug 7, 2025

By /Aug 7, 2025

By /Aug 18, 2025

By /Aug 18, 2025

By /Aug 7, 2025

By /Aug 18, 2025

By /Aug 7, 2025

By /Aug 18, 2025

By /Aug 7, 2025

By /Aug 7, 2025

By /Aug 7, 2025

By /Aug 7, 2025